How to know when to stop

A guide to avoiding burnout and establishing balance in your life

In 2018, the universe sent me a sign saying, “Slow the fuck down!”

I was recently promoted to president at Wealthfront after 15 hard years of climbing the startup ladder. Yet after only a few months in my new position, I was in the emergency room with heart issues.

After several tests, the doctors told me that my heart was like a lopsided tire. It worked, but it wobbled. Some parts of my heart were enlarged, and others had a thick, rigid texture that I imagine is like the low-quality meat you find in a bad bowl of pho.

The cardiologist gave me the “You know how many 40-year-old CEOs I know who have heart attacks?” talk. Except I was only 35 at the time. I knew that I was constantly stressed out and exhausted from work. But I was unaware of just how fragile my health had become.

He lectured me on what I needed to do moving forward. I needed more rest, more exercise, a better diet, and less stress. It’s advice that I already knew but that I ignored while in the “fog of war” of high-growth startups. Yet it was clear that I had had enough. So I stepped down and left the company to focus on my well-being.

Systemic imbalance

In retrospect, the signs were there that I was pushing too hard. I suspect the same is true for many of us in high-profile positions, high-profile startups, or high-stress industries.

To help prove that, I decided to run a few surveys on LinkedIn.

Nearly 50% of responders have thought about changing their careers at least three times due to “not being worth it.” And another 50% have cried because of work at least twice. It seems commonplace within our work culture to push ourselves to a breaking point, whether it’s physical or psychological. Often it’s both, as our body and mind are intertwined.

Nonetheless, as someone who was conditioned to always aim for the top, like many high achievers in the world of tech, I was having a hard time reconciling the limitations of my health with my professional ambitions.

It was clear that I needed to make a trade-off to avoid a fate that others had faced, like the sad loss of the wonderful Dave Goldberg at 47. It also required that I step back and take a holistic assessment of what matters to me. Not just with work but with the broader tapestry that makes up a complete life, including human connection and nurturing experiences.

So I created a framework to do so. It has three parts:

Define your personal range of tolerance

Pick your career progression

Pick your life progression

I should have followed these steps earlier in my life. But because of my relentless, single-minded pursuit of success, I had to do so somewhat retroactively. I hope this framework will help you avoid my mistakes and establish a balanced life that allows you to thrive in many dimensions of life, not just the professional.

Part 1: Define your range of tolerance

Stemming from my heart attack scare—a clear sign that I was overloaded—I began creating a plan to keep myself out of extended periods of unsustainable stress. That’s when I rediscovered the concept of a range of tolerance and started to apply it to myself.

After a few years of iterating on it and pursuing it earnestly, it’s led to a quality of life that I wouldn’t trade for any salary. Here’s more on how it works.

Where does life flourish?

Life is found everywhere on the planet, but it is not evenly distributed. That’s because life has an optimal zone to survive and reproduce.

For example, Atlantic salmon spend most of their adult life at sea, but they make an annual trek into freshwater to breed. Most other saltwater fish die quickly when placed in freshwater, but it’s a variable that the salmon are uniquely accustomed to.

Source: Shelford’s law of tolerance

Staying within a range of acceptable tolerance in your life should be the goal so that you flourish in all dimensions, not just the professional. Taking on too much pushes us into zones of intolerance, where very little life can be sustained.

How do I know if I’m outside my range of tolerance?

When pushed outside our tolerance range, we will experience a wide range of indicators.

One category of indicators is hormonal dysregulation, which reveals itself in the form of negative emotional states. We can feel irritable, anxious, sad, angry, withdrawn, or shut down.

The second category of indicators of unmanageable stress is physiological. Our natural bodily functions are interrupted, including the musculoskeletal, respiratory, cardiovascular, endocrinal, gastrointestinal, nervous, and reproductive systems.

Lastly, we may adopt destructive behavioral patterns to soothe our emotional discomfort. We may develop addictions or compulsive activities as a coping mechanism due to excess stress. I know a lot of people who need a bottle or two of wine several nights a week in order to “unwind.” That’s not healthy behavior.

Take an inventory of possible stress responses

In the first few months of receiving therapy, I quickly wised up to all the ways in which my mind, body, and habits were telling me that I was on a bad path.

My therapist sat me down and ran me through an inventory of my bodily sensations, taking note of my jaw and neck tension, tightness in my chest, shallow breathing, and huge bags under my eyes.

Next, she dissected my habits and behaviors. She expertly pointed out all the ways in which my work routine had sidelined healthy habits and replaced them with unhealthy coping mechanisms, such as smoking pot at night in order to sleep.

As the months and years went on, I became much more attuned to myself, which gave me the tools to assess how I was doing at any point in time. That turned out to be the first in a series of steps that I took to defend my health and know when to take a break.

Based on what I learned through therapy, and in conjunction with comprehensive research on the subject of chronic stress, I created a simple questionnaire that you can copy and use yourself.

Note that assessments like this can be subjective, so there isn’t a clear line in the sand that perfectly describes the state of your mental health. But they can be reliable indicators that someone may need to seek help.

There are also publicly available tests that are clinically used and approved and can be taken for free. The Beck Depression Inventory is widely used, as is the Patient Health Questionnaire. With many of these tests, if you score near the midpoint of the total possible score, you’re entering a clinical level of depression that professionals would deem worthy of treatment.

If you want to know more about the mind-body connection, Gabor Maté has an incredible lecture that discusses the relationship between trauma and our health. I suggest carving out an hour to give it a listen. He is one of the best in the world at discussing the human condition:

Here’s what my stress response inventory looked like in 2017 when I was on the verge of peak burnout.

I had checked 17 of 29 boxes, and I was still burning the candle at both ends. Eventually, I ended up in the hospital, which I could have avoided if I’d truly listened to what my body, mind, and behaviors were telling me.

Each person has a unique range of tolerance

We must remember that when we approach our lives as if we have a limitless range of tolerance, or that our tolerance must be the same as our peers, we’re pursuing our life and our work in an inevitably unsustainable way.

We’re all unique. Our biology, our circumstances, experiences, and the environment we are in will influence our range of tolerance.

Biological and environmental factors

My heart attack scare forced me to confront my biological limitations. It also helped me understand the direct connection between psychological trauma and physical illness.

The doctors gave me a half-assed guess that “maybe it was genetic,” but every part of my ass knew that it was the by-product of excess stress on my nervous system, beginning with the PTSD induced by my early childhood experiences.

Being not a complete idiot, and in deference to the substantial amount of research showing the connection between PTSD and cardiovascular disease, I listened to my doctors and stepped away from work. That was the beginning of admitting that my nervous system wasn’t cut out for the constant stress of a leadership role within the chaos of growing a startup.

Even as I write this, from the comfort of a couch in a local coffee shop on a beautiful Sunday morning, my heart pounds, and my chest feels entombed with pressure. It’s not because of my present circumstances. It’s because of the shadow cast on the most primitive components of my brain by certain experiences I had as a kid that left me with an overactive nervous system.

That’s the way it is for me.

Conditioning and negative beliefs

The beliefs we hold can be very harmful and limit our ability to cope with challenging situations.

A few examples of negative beliefs that I’ve commonly heard throughout tech:

“I guess my coworkers manage stress better than I do.”

“I have to accept feeling like this since it’s part of the job.”

“I hate this feeling and just want it to disappear, but I don’t think it ever will.”

Holding these beliefs can lead to further negative behaviors, such as withdrawal, avoidance, or even self-harm.

For example, there was a time when I called in sick at Twitter to avoid giving a five-minute presentation at the upcoming all-hands meeting. I was already sick with panic attacks, so the last thing I wanted to do was talk in front of a few hundred people. I decided to withdraw and bailed on my obligation to speak to the company. I told my boss that I had the flu.

In my mind, I was conditioned to think that I needed to be perfect; otherwise, I wasn’t worthy of acceptance and love. Already in the grips of panic attacks, it was easy for me to believe that my presentation would be a failure, so I bailed on it before I gave myself a chance to prove otherwise.

Create your tolerance list

Now that you have taken an inventory of your current stress level, it’s time to come up with a plan to keep yourself within an acceptable range of tolerance as often as possible.

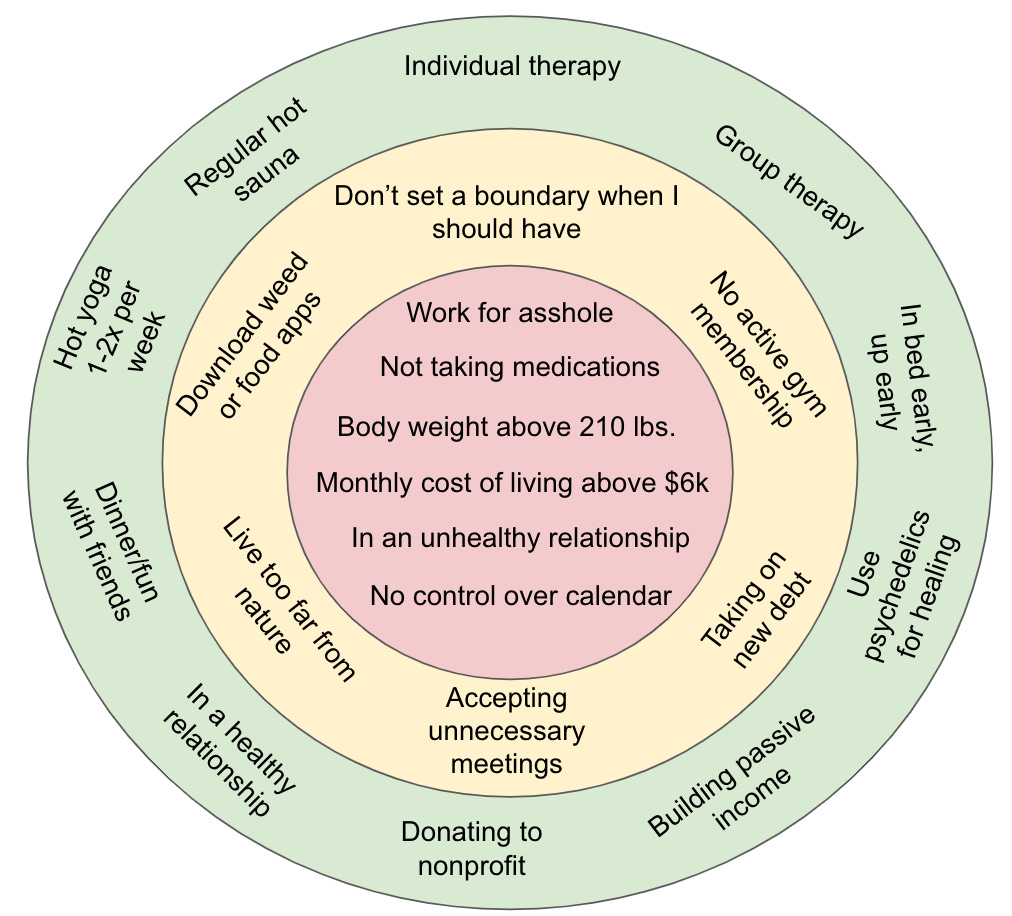

It begins with creating a few lists:

List of intolerables: A list of things to completely avoid. These are the variables that immediately place you outside of a tolerable range and should be avoided. Think of experiences you’ve had that have produced a large emotional response that sent you into a downward spiral. Or things that you intuitively know are bad for your overall well-being. This may also include negative coping mechanisms such as substance abuse or behavioral patterns that directly impact your health, such as binging on junk food.

List of boundaries: A list of self-imposed boundaries that are favorable toward health and well-being. These act as defensive measures to avoid the slippery slope into intolerable situations. For example, a boundary that promotes healthy behavior could be maintaining at least one active gym membership.

Plan to flourish: A list of items that put you in your optimal zone of performance. You should be prepared to make sacrifices in order to commit to these. Think of experiences or behaviors that make you feel healthiest and at your best. These are the items that, when you commit to them, make you more resilient against things that test your tolerance.

Here’s a table for creating your list. It is broken down into each major category of life to ensure that it is thorough and inclusive of a full life experience, not just our professional lives.

As an example, here’s the current list that I use to organize my life. I tend to update it every 6-12 months, but this is the list that I’m using at this stage in my healing and this stage in my life and career.

Create your tolerance target

Once the list is complete, transpose it into the tolerance target, which is a visual representation of the list you created.

Items in the center red circle, you want to avoid at all costs. Items in the middle yellow circle are those that may be a slippery slope toward intolerable experiences and should be navigated mindfully. The outer green circle is where you want to dedicate your time since that’s what encourages resiliency and allows you to flourish in all of life’s dimensions.

This is what my current tolerance target looks like. I’ve hand-picked the items that resonate with me as “most true” when it comes to my own range of tolerance. I’d encourage you to do the same thing by trimming your list down to the items of greatest importance to you.

For example, I once had a boss publicly mock me in front of my peers for not knowing how to write a very complex SQL query. It wasn’t playful banter. It was public ridicule. I asked him to speak with me privately. I pressed him on how unacceptable it was for him to publicly mock me. He shrugged and said, “Well, that’s just the way I am. I don’t know what to tell you.”

Two weeks later, I put in my notice that I was leaving to join another startup. That clown was naive enough to act shocked and angry that I was leaving. After repeated negative interactions with him that made me feel stupid, I decided it wasn’t worth the bullshit, so I left. Sometimes that’s the right thing to do.

As a result, I put “Work for asshole” in the negative red center of my diagram. It’s not what brings out the best in me, nor does it lead to an enjoyable work environment, so I refuse to do it anymore.

Your red circle is for experiences that you find are deal-breakers when it comes to your overall well-being. I left quite a bit of money on the table by leaving the company when I did, but I found much more peace and self-confidence on the other side.

Part 2: Pick your career progression wisely

Now that you have an understanding of your range of tolerance, and a list of things you can do to stay within your range, consider how your broader life choices will fit into your tolerance target.

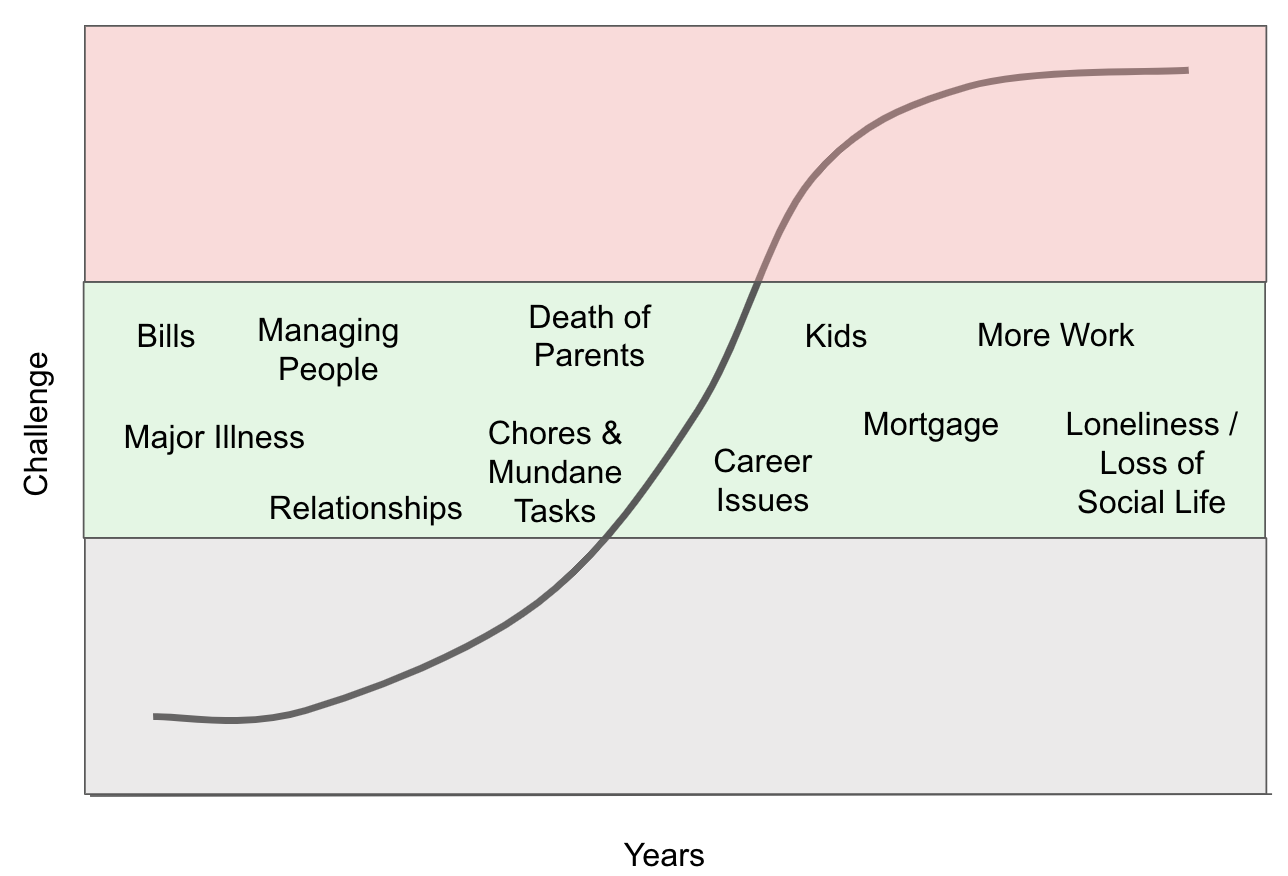

It begins with a concept I’ll refer to as the “career S-curve.” It’s a measure of how much “stuff” we take on during different stages of our careers.

On the y-axis is “labor” from low to high. The x-axis is years (into life or career).

Generally speaking, we can break our career into three stages along the career S-curve.

The first stage is setting a foundation in terms of getting your career started.

The second phase is the acceleration phase when we tend to push to climb the ladder.

The last phase is the peak phase, where we slow things down and ride the coattails of our prior work.

We can also generalize the types of responsibilities at each stage. As time goes on, we evolve from developing skills and doing individual-contributor work to something entirely different.

During the acceleration phase, people tend to start managing other people and managing projects of increasing scale and complexity.

At the peak phase, it presumes that you’ve climbed high enough to where there isn’t much climbing left to do. At this level, you’re managing entire organizations instead of small groups of people. And although you may still be managing some large projects at this level, a huge portion of what you’re doing is managing problems that keep getting bigger and more frequent the higher you climb.

The amount of labor and hours tend to increase as well. There are two types of hours that increase. Let’s call them “office hours” and “mind hours.”

Office hours are the standard measure of the number of hours you’ll work where there’s a “butt in a seat,” i.e. actual work being done. We tend to work more office hours as our career progresses toward the peak.

Mind hours are the number of hours that your mind and nervous system are preoccupied with work because of the stresses of it.

What most people in the acceleration phase of their career underestimate is the number of mind hours that are spent working, especially if your goal is to get to an executive level, which is in the deceleration phase (there’s only so high you can go). You may work 50-60 hours a week, but you may have to tack on an additional 10-30 hours of mind work on top of that.

The thing about mind hours is that they are the most emotionally taxing. You’re worrying about who to hire and fire, projects going off the rails, a CEO who’s on a rampage, and so on.

Nights and weekends, which earlier in your career during the foundation stage were used to recover from office hours, are now spent on mind hours, eliminating most of the room for proper rest and recovery at an intellectual and emotional level.

As an overachiever, you’re probably thinking, “Well, of course I’m going to be an executive. That’s what successful people like me do.” Sure, you can do it. But the better question to ask is whether you should.

Part 3: Pick your life progression wisely

Determining if you should keep climbing the ladder is partly answered by understanding what the trade-offs and consequences are. After all, the career choices you make have an impact on other facets of your life.

Let’s turn to the S-curve of life, which is a similar model but applied to non-work-related aspects of living. It is also broken into three basic buckets.

In childhood, life is full of mystery and exploration, and everything is exciting because it’s new. On a relative stress scale, young life tends to be easier than adulthood. Not always, but often.

The acceleration phase is when you’re pushing well into adulthood and midlife experiences. That’s often characterized by major expenses such as cars and homes and is when the precariousness of life becomes more evident when people have accidents, get sick, encounter major hardships, and have to respond to various fire drills (losing a job, kids getting sick, etc.). All of which are taxing on your mind and body.

Lastly comes the peak stage of life. We and others begin to decline physically and we prepare to pass on our legacy to, if we're lucky, our family and friends.

When worlds collide

It’s roughly between our late 20s through our 50s when these two S-curves collide. We take on more not only at work but also outside of work. We walk ourselves year by year into overload, especially as overachievers within a culture that encourages achievement as a defining element of a life well-lived.

Our ability to take on a lot is thoroughly tested. As high achievers, we’re conditioned to not question if we should take on more. We just put our heads down and run face-first into exhaustion without pausing long enough to ask ourselves, “What am I doing? And why am I still doing it?”

Benefits of periods of intolerability

All of that said, I’m not arguing that we should avoid any period of intolerability. There may be times when you decide it’s necessary to expose yourself to harsher conditions. But that’s the key—you should consciously decide when and why a wander into the intolerable makes sense.

In biology, there is a concept called hormesis. What it refers to is that all organisms have adaptive mechanisms that kick in when the organism is put under a reasonable amount of stress, and those mechanisms are adaptations that may improve the organism’s tolerance or performance. A common example would be exercise when it comes to increasing muscle mass, bone density, and cardiovascular capacity.

In a professional context, there are times when it makes sense to seek situations that can produce a “hormetic career response.” There are promotions or new roles that you may seek that require a step up in effort and responsibilities, and you may determine that it’s worth the extra stress and work to pursue it.

Intolerability example

Let me provide a personal example.

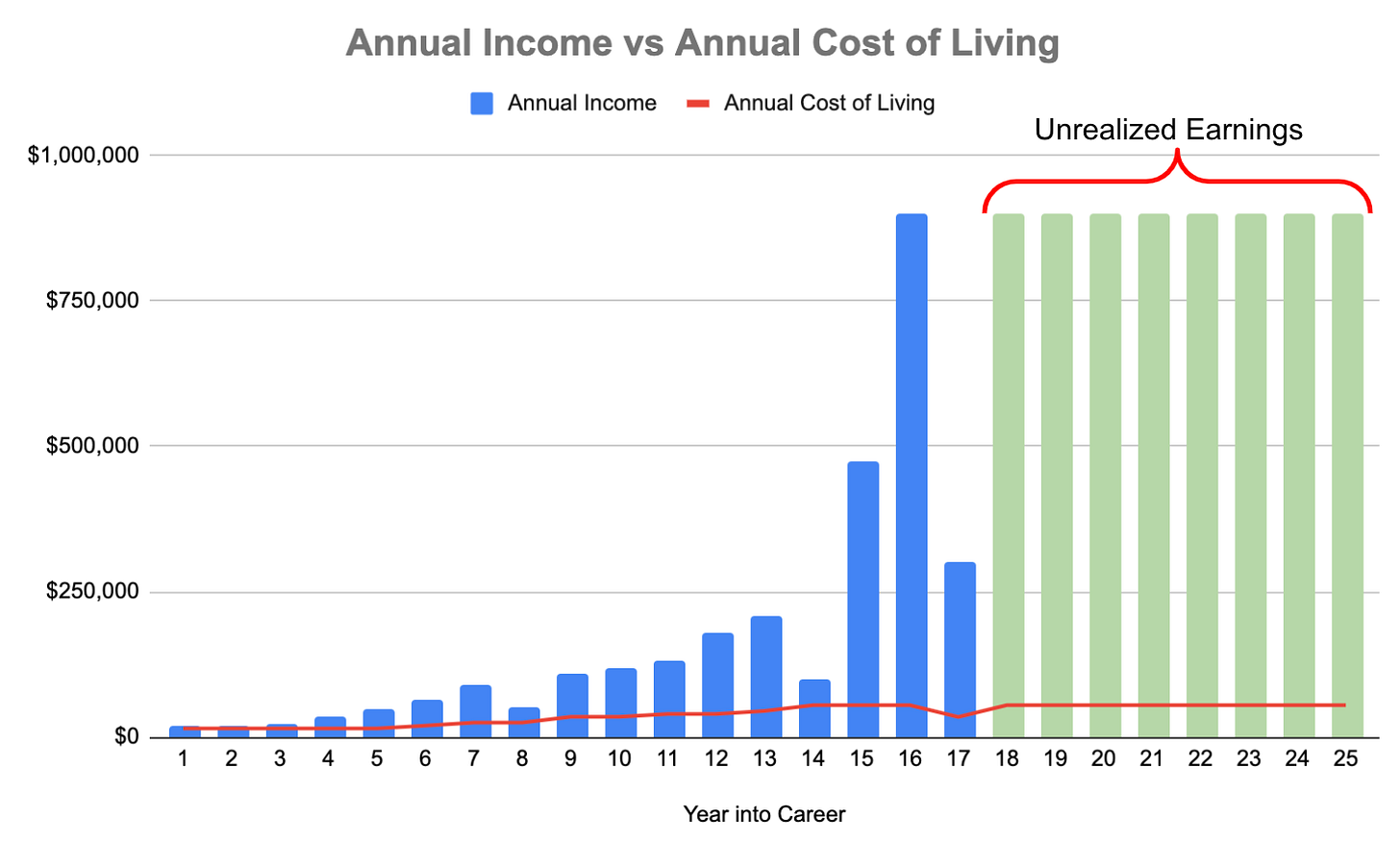

Early in my career, I made a decision that I was going to establish financial freedom as quickly as I could. I understood that it meant increasing my earnings from work (via promotions) while keeping my lifestyle costs as low as I could. I would then aggressively invest my savings to build a modest nest egg.

Here’s a plot of my actual earnings vs. cost of living per year since the beginning of my career.

The first green row and the second green row are when I took 6+ months off that year to recharge. I left Quora during year 8 of my career because I was having lots of panic attacks and bouts of depression and struggling with my OCD. And I stepped back from Wealthfront at year 14 of my career due to the heart issues I wrote about above, which were driven by long periods of excess stress.

As a result, my earnings were lower during those years. The last green row, in year 17, is when I declared that I had enough money saved such that I could live a simple life off my savings and not have to work as hard anymore to build my nest egg.

I also kept my annual cost of living low relative to my earnings, especially by the time I was about 10 years into my tech work. I made the decision to not own a home in the Bay Area, keeping me from having to pay for a $1M+ jumbo loan, which would have required more years of work that would regularly push me outside a tolerable range of stress.

You’ll also notice that there were three different acceleration phases in my career. Those are the periods when I made a push into new jobs, higher levels, and higher pay. Those periods also coincided with higher stress, leading to major burnout and the need to step back for rest and recovery. My nervous system was totally shot by the end of each period.

Going back to the S-curve metaphor I shared earlier, it would be more accurate to say that a career is a series of S-curves stacked on top of each other.

As you can see from my personal example, I had three major S-curves. However, I decided to call it quits shortly into my third major S-curve since the benefits no longer outweighed the costs.

In the early stages of my career, I experienced many benefits from the acceleration pushes. I paid off school loans, gained new skills, expanded my network, and increased my earnings. And I moved closer to my ultimate goal of financial independence one year at a time. But by the third push, I could no longer justify the juice being worth the squeeze.

So I made another major lifestyle change in 2020 when I moved to a small blue-collar community with a significantly lower cost of living relative to Silicon Valley. With what would have been a down payment on a home in the Bay Area, I was able to purchase my home outright. The same type of home costs four times as much in the Bay Area.

That meant I had no mortgage to worry about, which is a major expense that keeps most people locked into doing work that may drive them outside their acceptable range of tolerance.

Now, as long as I make at least $35,000 a year post-tax, I won’t have to dip into my savings or investments at all.

Note that I also assumed that the equity I held in the startups I worked for would be worth $0. That was a conservative assumption that drove me to keep my cost of living low relative to my earnings. Anything that comes in from stock options will be icing on the cake.

So, before you make your next major career or life decision, pause and ask yourself a few questions.

How much money do I truly need to live the life I envision for myself?

What would I have to sacrifice if I reduced my salary in half, and would it be worth it?

What would I need from my job in order for it to be worth the extra labor and stress?

Saying no to the unnecessary

In 2020 I began having significant mental health issues again. It was brought on by a combination of excess stress and overwork, and isolation brought on by Covid made the situation worse.

Had I decided to continue working at the level I was, I was guaranteed to earn a lot each year—somewhere just short of $1M. If I continued for eight more years, until my 25th year of work, my gross earnings from salary alone would have ballooned.

In the below example, I would have earned about $10M in cumulative salary during my entire career, with 70% of my career earnings being in the last eight years.

However, since I decided to take a major step back to focus on my health and not continue with the same stressful lifestyle, I am no longer earning nearly that much per year.

Yet it was worth it. Within 30 days of making several major lifestyle changes to focus on my health, my blood cortisol levels, which is a dominant stress hormone, dropped by 30%. And I finally had months of dedicated time to work through the childhood trauma that had been taxing my nervous system for decades.

That’s the beauty of knowing when to say “enough is enough.” Given my modest lifestyle goals and my desire to focus on my health, I was able to call it quits with the stress of running high-growth startups and giving my nervous system the rest that it desperately needed. And I was able to make a complete investment in the other aspects of my life that had been neglected for years.

How to develop more tolerance

Although there are benefits to windows of intolerance, we should still aim to remain within the range of tolerance as often as possible. To do so, you can widen that window in a couple of ways:

Lower your baseline agitation

Reduce recovery time from peak stress

Lower your baseline

This means lowering your default state of agitation. I’m more anxious than the average person (I have PTSD and OCD diagnoses), so my tolerance range is narrower than I’d prefer. To widen it, I try to engage with my green-circle items as much as possible.

Hot sauna and hot yoga are mainstay techniques for me. The reason for that is I find them effective at lowering my baseline heart rate without the wear and tear of a traditional workout. Most of the time I’m walking around with what I refer to as “PTSD heart” (it’s rapidly beating from fight-or-flight mode even though everything is OK). With a hot sauna or yoga session, I experience a meaningful decline in my resting heart rate once I’m in the recovery period. It tends to last for a few hours at a time and sometimes for the rest of the day. A 20-year study involving 30,000 people in Japan demonstrated a 28% decline in cardiovascular disease for those who took a sauna every day versus those who didn’t.

For me, it’s a green-circle behavior that I stick to religiously for the impact it has on regulating my nervous system. I could say more about it, but biochemist Rhonda Patrick does a better job, so listen to her instead.

Reduce recovery time

Professional fighters know how important it is to recover quickly between periods of high exertion. A five-minute round pushes most fighters into an intolerable physiological range, so they have to become skilled at recovery to approach the next round fresh and ready to fight again.

Although I’m using athletes as an example, the concept of recovery from excess stress applies to anyone experiencing a high range of physical and/or psychological stress. Without a serious commitment to recovery, we can’t expect to improve our ability to bounce back from periods of intolerability.

The good news is that by drafting your tolerance list and turning it into a tolerance target, you can create a lifestyle that not only manages the frequency with which you’re brought into intolerable periods but also gives you the tools to quickly recover from high-stress periods, which in turn improves your range of tolerance moving forward.

Knowing when to stop

There will be times when it makes sense to push very hard on career growth, so long as it aligns with the vision you have for your future and respects the boundaries of your range of tolerance.

The purpose of life isn’t to sacrifice our well-being. The purpose of life is to flourish.

But it requires sacrifices to be made. Maybe you should turn down that promotion. Or not buy that house that will bind you to 5-10 years of additional work to pay for it. It may also require separating ourselves from people whose lifestyle preferences are misaligned with our own.

It can be done as long as you understand your limitations and make conscious life decisions that align with what enables you to flourish. And when the time comes to call it quits, you will feel secure in saying, “No thanks. I’ve had enough.”

So I have been working in the US for last 8 years and one thing I note is - somehow Americans love the idea of work. It is like deeply ingrained into them. Back in India, from where I am, the idea of work is to make sure we get some activity done in a day, and then rest of time is spent with family, friends and also pursuing spiritual practices like meditation and studying philosophy.

I understand, due to the work ethic of Americans they have built a country which is most rich and is some sort of super power, but at the same time when I meet with my fellow American coworkers, I see all of them suffering from some sort of neurosis.

Maybe a broader picture of life needs to be presented where “work” is a piece of puzzle and not everything.

"I was conditioned to think that I needed to be perfect; otherwise, I wasn’t worthy of acceptance and love."

This is IT. I was just reflecting on how my imposter syndrome didn't materialize as a result of the treatment I received at certain jobs—rather, it was the reason I pursued and stayed at those types of jobs (and relationships, but that's another story) to begin with. I needed to be perfect, and perfect will always be an impossible target.

I've had similar experiences before 5-15 minute presentations (over Zoom, with notes) when I reached the height of my career as a Creative Director. I would practice obsessively over and over, burst out crying throughout the day, and get very close to bowing out before giving what appeared to be an easy, natural performance and receiving tons of praise. My success never made the next one any easier, it was just a new bar to live up to.

Other people may have a higher window of tolerance because they just don't CARE as much as we do. I've noticed those people aren't particularly good at their jobs, though. The trick, I think, is to care for the right reasons—not because you need to prove that you're enough, but because you have a genuine calling to solve problems. It will still be inherently stressful, but more of it will be that positive type of stress that doesn't screw with our nervous system. And to your point, moving on when the culture is not respectful, let alone balanced, is paramount.

Personally, I wound up with Long Covid. Even then I pushed through 2 years of shortness of breath, crushing fatigue, elevated heart rate (150-170 bpm), digestive issues, and anxiety. I finally got laid off (an ego death, but better than a real one), and became bed ridden. My body was completely shot and made the decision for me. A year has passed and I'm still recovering.

We tend to take our health for granted until we have a big scare like yours, or mine. I hope more people come to understand that we are inherently worthy, and there is as much value in being (how we care for ourselves and show up in the world) as in doing.

Thank you for this excellent, vulnerable contribution to the topic of tech and burnout! I'm going to share it around.